Hope & Skepticism: Using Generative AI for Scholarly Work

In December 2022, Bill Tomlinson, an informatics professor at UC Irvine, was struggling with a research paper. The research — conducted in collaboration with Andrew Torrance, a law professor at the University of Kansas — involved exploring whether a large language model could interpret animal communication and how that might influence animal rights law.

“We had been trying to get this paper out for months, but we’d only written about two paragraphs,” says Tomlinson. At the time, he had recently started playing around with a new tech tool called ChatGPT. So during his next meeting with Torrance, he suggested using the AI-based chatbot to generate some text related to their research.

“That really got the ball rolling,” says Torrance. “Bill took the bull by the horns, or took the ChatGPT by the query, and got us moving.”

The pair, who have been working together for years, have since gained a much better understanding of how to leverage ChatGPT for academic papers. They’re now sharing what they’ve learned in a series of papers written in collaboration with Rebecca Black, a colleague of Tomlinson’s in UCI’s Donald Bren School of Information and Computer Sciences (ICS), and Donald J. Patterson, CTO at Blockpliance and a visiting associate professor in ICS. The papers cover AI as it relates to everything from scholarly writing and carbon emissions, to fake news and knowledge production, to issues of governance and AI training.

Best Practices & Legal Pitfalls

Tomlinson and Torrance readily admit that ChatGPT was immediately useful in helping them generate text. “Coming up with 15 or 30 pages from scratch is challenging,” explains Tomlinson, “but if AI writes the outline for me, I can say, ‘That’s not what I wanted. No … like this!’ and 45 seconds later, I have a new draft.”

However, they also quickly realized the many pitfalls of using AI. They had to take various precautions to ensure the work remained legally and technically sound, particularly in terms of the citations. “That’s one of the things that, traditionally, ChatGPT is really bad at,” says Tomlinson. “Andrew is an intellectual property lawyer, so it would look bad to violate intellectual property in his scholarship!”

Through their experience, they identified ways to ensure quality control, comply with copyright laws and maintain academic integrity. Working with Black, they translated what they learned into a framework to share with other academics.

“We developed a set of best practices for how to make a paper that is ideologically defensible,” says Tomlinson. They outline their findings in “ChatGPT and Works Scholarly — Best Practices and Legal Pitfalls in Writing with AI,” published in SMU Law Review Forum.

The first citation of the paper clearly states: “We wrote this article in collaboration with ChatGPT.” The paper goes on to provide a guide for avoiding plagiarism, and it presents a well-researched framework for establishing sound legal and scholarly foundations.

Environmental Concerns & Controversy

As the researchers developed their framework to address Torrance’s concerns around the legal side of ChatGPT, they also had to tackle Tomlinson’s concerns around AI and sustainability. “I was pretty sure it’s an environmental blight,” says Tomlinson. He recalls telling Torrance, “I’m not going to be able to make this part of my professional work if every ChatGPT query is like flying to France and back.”

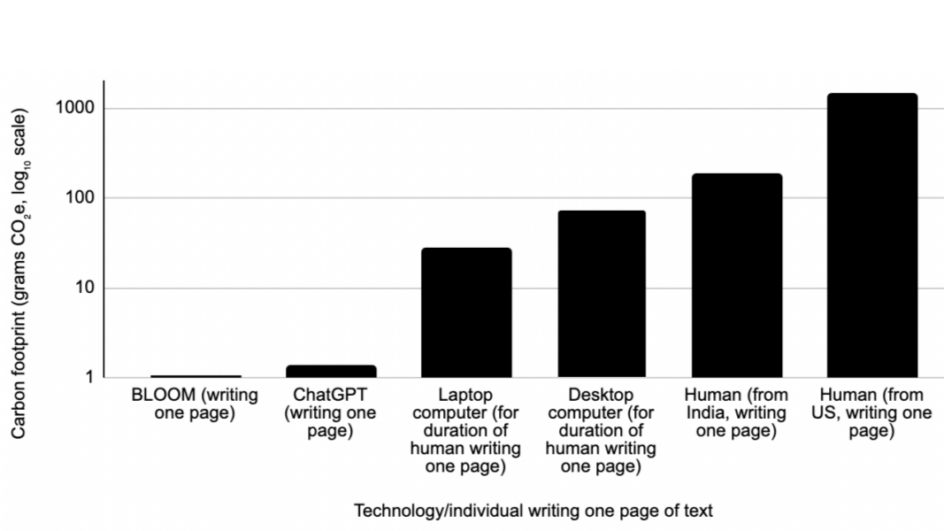

So as they have done over their many years of working together, they created a hypothesis to test their assumptions. Collaborating with Black and Patterson, they analyzed the carbon emissions of several AI systems (ChatGPT, BLOOM, DALL-E2 and Midjourney) and compared them to human collaborators. The findings surprised Tomlinson.

“It is not necessarily the environmental blight that people sometimes say it is when you compare it to a human collaborator,” he says. “If you compare it to a word processor, it’s a train wreck. But it’s not serving the role of a spell checker or a word processor. It is serving the role of a human collaborator.” They found that AI writing a page of text emits 130 to 1,500 times less CO2e than a human doing so.

Their findings, outlined in “The Carbon Emissions of Writing and Illustrating Are Lower for AI than for Humans” (currently in a second round of review with Nature Scientific Report), are already causing controversy.

Yann LeCun, the chief AI scientist at Meta, called the work “very interesting” in a post on X that currently has more than 645,000 views. “It’s been a tumultuous set of discussions,” says Tomlinson, “but ultimately none of it has caused me to feel like the core analysis in the paper is incorrect.”

The researchers, however, welcome additional scrutiny of their work. “The best thing that could happen coming out of this study is that people dig further,” stresses Torrance. “We do this transparently, using objective methods, and we leave it open to other people to take the baton further.”

How AI is Shaping the Future

Torrance views AI as the latest in a long progression of things that make research and writing easier, ranging from libraries and typewriters to moveable type printing presses. “All of these things are leaps forward that potentially free up the human mind to do what it’s best at, expressing itself in creative work,” he says. “It takes some of the mechanical work and makes it frictionless and more efficient.”

Tomlinson remains skeptical. “One of the challenges with it, though, is that with the Internet, it will be very easy for many entities to put out content that is garbage instead of taking that extra time to refine the work,” he says. “It could create a situation where the average quality goes down.”

Tomlinson has already seen questionable behavior, noting that one author cited himself multiple times for “cutting -edge” work in AI. “We can say whatever we want [with] authority, and that authority will carry through into future AI systems. So this person may very well have been getting themselves citations in 2050,” he explains. “It was really interesting to realize [how] content becomes part of future training sets, and that can be a mechanism by which these training sets become fake news in the future.”

Fake news and knowledge generation are among the topics Tomlinson and Torrance, at times in collaboration with Black and Petterson, cover in a series of forthcoming papers:

- “Turning Fake Data into Fake News: The A.I. Training Set as a Trojan Horse of Misinformation” (San Diego Law Review),

- “Late-Binding Scholarship in the Age of AI: Navigating Legal and Normative Challenges of a New Form of Knowledge Production” (UMKC Law Review),

- “Governance of the AI, by the AI, and for the AI” (Mississippi Law Journal), and

- “Training Is Everything: Artificial Intelligence, Copyright, and Fair Training” (Dickinson Law Review).

The main message Tomlinson hopes to convey with this work is that change is coming. “There will be important changes — some will be able to benefit society, and others will be harmful — and it’s important to have a critical eye to tell which is which.”

Torrance offers a different takeaway. “We have conducted an experiment over the last six months, the experiment being that we used the latest generative AI to generate scholarly writing,” he says. “It’s been an incredibly fruitful experiment to see what you can do if you adopt this new technology and you put it into a well-known area like academic writing.”

The experiment has indeed been fruitful. In addition to these accepted articles on AI, the researchers have another five papers in the works. “What’s exciting about this next set of five is that they’re on biodiversity, which is the core of what we think is important in the world,” says Tomlinson. “We also still haven’t published that first one on whale communication!”

Torrance notes the irony of the situation. “That research came from the direction of, ‘Could we use AI to understand or talk to animals?’ and then everything got kind of subverted to the point where now we’re using AI so that we can talk.” They’ve since returned to that first paper and plan to finalize it by the end of the year, as their conversations with — and about — AI continue.

— Shani Murray